In part two of our series on municipal taxes, we look at how COVID-19’s impact on municipal revenue streams could be significant

By Terry Troy

Like many victims of long-term COVID-19, our state’s municipal tax system will soon start to feel the continued impact of the pandemic if some forward-thinking remedies are not soon put into place. Let’s be honest, Ohio’s municipal tax system wasn’t in the best of health any way. But the pandemic did open something of a Pandora’s Box, exposing many pre-existing problems with the system.

“No. 1 is that municipal taxes in Ohio stink,” says Brad Hoffman, a CPA located in Columbus who also has practices in Florida. “The only state worse is the state of Pennsylvania with their township taxes. They have four different agencies collecting money and figuring out how to withhold it—it’s just a nightmare.”

“I have been at this for more than 22 years,” says another Columbus area CPA requesting anonymity. “It’s not so much that it is confusing to me, but I am sure that to people who are fresh in the game, it is very daunting. I also know that tax preparers from outside of state want nothing to do with Ohio because of the municipal tax situation.

“You really have to understand it to work with it, and by that I mean that you can’t just work with it for one season, because you simply won’t get all of the nuances.”

New hybrid work situations, where people split time between the office and remote or home work, are certainly not helping the situation.

“The number of incorrect W2s are definitely way up,” adds Hoffman. “Employers don’t keep track of exactly where people are working every day.”

Certainly the remote work created by COVID is not a unique situation. Construction workers, tradesmen and service professionals have long paid taxes in the cities where they performed work. It’s just that more office workers today split their time between the office and remote locations.

The latter issue has caused some consternation among municipalities, some of which might experience shortfalls in the near future.

“The shift to remote working has the potential to significantly shrink the tax base for large and small cities in almost every corner of the state,” says Keary McCarthy, executive director of the Ohio Mayors Alliance & Ohio Mayors Alliance Foundation. The Ohio Mayors Alliance is a bipartisan coalition of mayors in Ohio’s largest urban and suburban communities.

—Keary McCarthy, executive director of the Ohio Mayors Alliance & Ohio Mayors Alliance Foundation

“Remote working can be a good thing for workers, but it can also have real fiscal consequences on our cities and the public services they provide. As we monitor these trends closely, we are also researching solutions to protect the fiscal health and long-term financial stability of our cities.

“There’s no question that the pandemic accelerated the trend of remote working,” McCarthy adds. “There’s little doubt that some workers will continue working remotely well into the future. However, it is not yet clear how significant this shift will be and what the long-term fiscal impacts remote working will have on many Ohio cities.

“The report we commissioned last year helped us understand what the potential fiscal impacts could be based on the trends at the time and feedback from the employer community. How employers and employees are determining their work location is still a moving target and will require ongoing analysis, including how hybrid work schedules might impact our cities.”

Published last fall, that study found that one-third of Ohioans don’t plan on going back to the office when the pandemic ends. They plan to work from home at least one to two days a week.

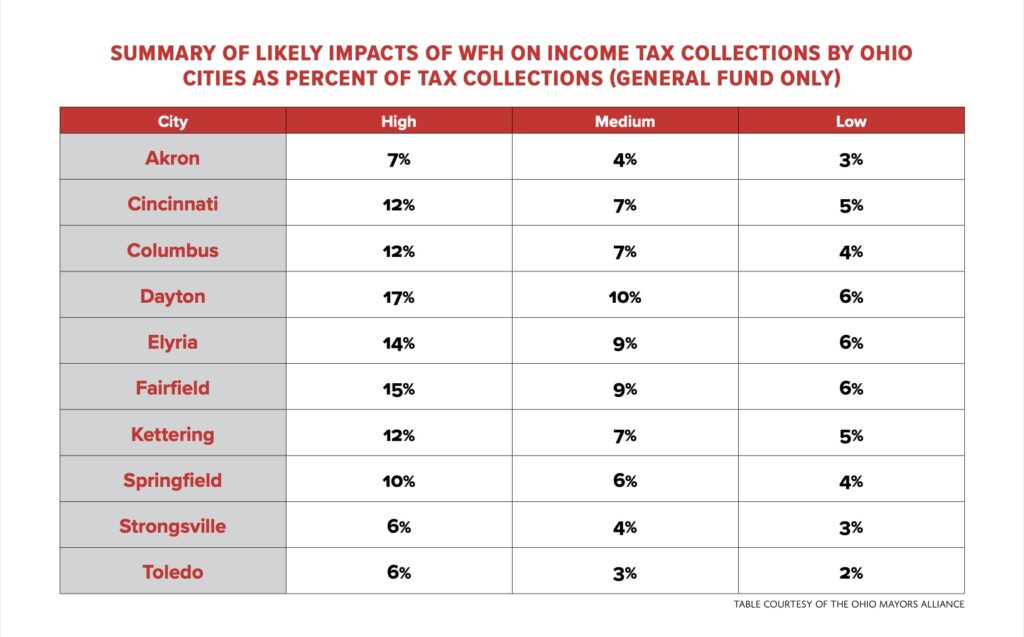

Researchers analyzed 10 cities from across the state and found that, on average, 33% of workers wouldn’t be going back full-time. Cities included Akron, Cincinnati, Columbus, Dayton, Elyria, Fairfield, Kettering, Springfield, Strongsville and Toledo. The resulting fiscal impacts vary by city, but range between a loss of 6-17% of municipal income tax revenue within a city’s general fund.

A breakdown of the budgetary impacts by city is included in the table in this feature. It shows a range of potential impacts from high to low, with most cities potentially seeing general fund revenue losses of more than 10%.

Dayton is expected to see the highest loss at 17%, while other cities like Fairfield (15%) and Elyria (14%) could also see significant budgetary reductions. Cities like Akron, Toledo and Columbus have additional exposure above these levels because they should also expect lower income tax revenues in places outside the general fund.

The report also states that the results provide a “very conservative” analysis of the overall impact that it will have on Ohio’s cities. This is because the report focuses solely on the loss of municipal income tax revenue paid by residents and non-residents. It does not address potential losses in the portion of the municipal income tax generated by business net-profit withholdings, nor does it account for potential follow-on effects such as less spending on goods and services in downtown business districts, an increase in office vacancy rates and decreasing property values, all of which impact parts of the local economy and employee earnings.

On the upside, the study also found that working from home increased productivity and employee satisfaction in a significant percentage of the population.

Even McCarthy admits that working from home isn’t necessarily a bad thing. However, he also points out that it has unintended consequences that will impact cities, downtown businesses and local economic development strategies.

The vast majority of firms across the country and in Ohio have implemented or plan to implement some form of hybrid staffing for their office-type employees, according to the report.

It’s also an issue being addressed by the Ohio Society of CPAs, especially with the rule changes happening this year—or perhaps I should say coming back this year.

“The withholding rules that are in place this year are actually what have been in place for years,” says Greg Saul, director of Tax Policy for The Ohio Society of CPAs (OSCPA). The organization represents 85,000 CPAs and accounting professionals who are the strategic financial advisers to Ohio’s leading businesses.

“What was in effect during COVID was basically a hold on the current laws. It allowed the employer to continue withholding at the business location during 2020 and 2021,” he adds.

The real issue, says Saul, is that many traditional office workers will now see these new withholding rules for the first time.

“They used to report to an office, and the withholding was always done at the office,” Saul says. “Now that there is remote working their employers will have to withhold in either the office, at the remote location, or in a hybrid situation where the employee splits work between a number of days in the office and the number of days at the remote location every week.

“What is going back into place is basically what tradespeople like plumbers, construction workers and electricians have had to deal with for decades.”

So when might cities and municipalities be impacted and how much could they lose?

“I don’t really think we have seen the impact as yet,” says Saul. “And we certainly don’t know the extent of it.”

Hybrid work does open a host of complex issues that could only make a bad situation worse, creating individual refund situations and issues that are unique to each employee as well as the location of their remote work.

“Getting a refund could depend on the tax rate of the municipality and whether your city offers a reciprocity credit,” says Saul. “For example, the tax rate in Columbus and the tax rate where I live are both 2.5%. So when I was working in the office, all 2.5% was going to Columbus because my city gave me 100% credit. So I didn’t have to pay any money to my resident city because it has the same rate and it gives 100% credit. But now my resident city is actually getting revenue from me because I set up my withholding to be 50% to Columbus and 50% to my home. So there is a revenue shift to another city.”

And remember, the equation gets even more complex when you talk about withholding at different rates based on the amount of work you do at your remote or home location.

“A lot of people are choosing 60/40 or 40/60 in terms of the time spent at the office or in a remote or home location,” says Saul. Which amounts to two days in the office or three days at home or vice versa.

That one example is just one of some 14 issues that need to be addressed when it comes to hybrid working schedules. The OSCPAs’ Municipal Income Tax Withholding & Refund Q&A Guide dedicates an entire chapter to typical hybrid work issues, covered in Q&A format from numbers 31 through 44.

Typical issues include whether an employer, under a typical hybrid schedule, must withhold for both the office and remote municipality throughout the year or whether the employer could choose a primary municipality throughout the year. The answer, according to the guide, is that they must withhold for both.

Another issue covers whether the 20-day Occasional Entrant Exception protects an employer from having to withhold to an employee’s home location. The answer is no, the 20-Day Occasional Entrant Exception will not protect employers from having to withhold to both the office and home location throughout the year.

“And that’s primarily because workers are going to hit the 20 days out of the office very quickly,” says Saul. “That’s why the legislature froze the withholding at the business location for a couple of years. The law went back to how it normally was, and the 20-day rule is still there, but in a typical hybrid situation, the 20-day threshold will be reached very quickly.”

However, the 20-day rule could still apply if the hybrid worker were to go to another temporary work location.

While the OSCPAs’ Municipal Income Tax Withholding & Refund Q&A Guide lays out these issues in a very understandable format, it is only available to the organization’s members. So it pays to get a member of the organization for help, especially when it comes to municipal income taxes. Indeed, even the OSCPA offers disclaimers in the guide’s usage.

“And the reason we put disclaimers in the guide is because it lays out the law as we understand it,” says Saul. “There are more than 600 municipalities that have an income tax in Ohio, and they are all administering their own taxes. How they interpret the law has not always been the way that we interpret the law.”

While the guide is extremely helpful, more help is clearly in order especially with the complexities at hand.

“This is one of the most unique and complicated areas of taxation, and it is specific to Ohio,” says Saul. “There are only 10 or so states in the U.S. that even have a municipal income tax and ours is pretty complicated.

“We have been trying to simplify it and make it more uniform over the years, but it is still something of a trap for the unwary.”

Saul and the OSCPA have been true to their word, supporting legislation in the past that updates the centralized collection process for levying municipal income tax based on a business’s net profits.

As for any municipality revenue shortfalls, “the municipalities might be able to make up some funds from either the federal or state government,” says Saul. “But I think, if we want to establish something more substantial moving forward, there will need to be a discussion with the state government.”

There are a quite few other CPAs out there who have more succinct opinions on the topic.

“I think they ought to follow the Florida, Tennessee and Texas models and just stop having to file income taxes,” Hoffman says. “Just tax the real estate and simplify it.

“I have a license in Florida. You know how many personal income taxes you need to file there? Just one, and it’s a federal return. You know how many you have to file in the state of Ohio? Three, if you live in a municipality that also has a school district tax.

“Ohio has been trying for years to bring it all into one form, but each municipality wants to have someone on their payroll doing it. So you get a lot of people objecting to what would be simpler and more honest.

“Sometimes, I spend more on a municipal tax return than I do on a federal return, and for only a small amount of money.

“How do I justify that with a client?”